What is Fairyland?

a quick primer on why i think the internet is fairyland

I am so thrilled with the reception of my New York Times piece but I did learn that people are both unfamiliar with the concept of an “otherworld” and Fairyland more specifically.

I got lots of love but also quite a few snarky comments, too.

I won’t display all of them but here are a couple of highlights — just for fun:

These people didn’t read the article (who amongst us hasn’t pulled that move, to be fair) but, more saliently, they also don’t know what Fairyland is. And why would they?

So, for my haters and my readers alike, here is the least exhaustive possible guide on the Internet as Otherworld, written when I was pregnant with my son, many moons ago…

WHAT IS AN OTHERWORLD?

An otherworld is a layered reality—it’s in the name: other-world. There’s the physical world we move through, and over it sits another realm—immaterial, ever-present, and constantly intersecting with the material while still remaining separate.

This isn’t an obscure idea. You already know the pattern. Narnia is an otherworld. So is the Wizarding World. Mythologies are full of them: the Welsh Annwn, Fairyland, the Irish Tír na nÓg, the astral planes of Western esotericism.

Across cultures and eras, people have assumed that unseen realms exist beyond human control—and that they matter. Because this belief is so old and so widespread, we’ve accumulated enormous cultural toolkits for navigating these realms. Mythology, fairytales, folklore, esotericism, superstition: they’re all practical guides for dealing with forces you can’t touch but that still shape your life.

Modern people usually dismiss this knowledge as irrational or outdated. But that’s because we haven’t recognized the otherworld we’re all already living inside: the Internet.

WHAT IS FAIRYLAND?

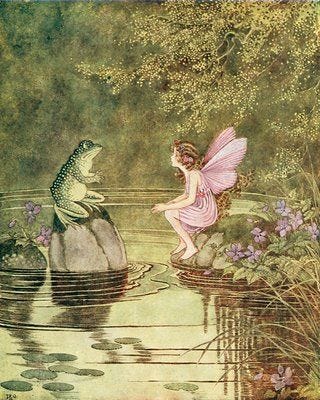

I was really surprised to learn that people still think of things like this when they hear “Fairyland”:

Or maybe this?

Or God forbid this…

Fairyland, as it actually appears in folklore, is nothing like the pastel, winged-creature playground the Victorians invented or appeared in whimsical ‘80s cartoons. The “real” Fairyland is older, stranger, and far less sentimental. It behaves more like a foreign country with its own politics, dangers, and etiquette than a glittery refuge for make-believe.

In the older stories, fairies aren’t tiny, harmless sprites; they’re powerful, amoral beings whose motives rarely align with human interests. If you’re a regular reader of my blog, then you’re already familiar with this characterization.

Fairies are beautiful the way natural phenomena are beautiful—dangerously, impersonally, without concern for you. Their world obeys different laws of time, ownership, and obligation. Eat their food, and you may never come back. Step into their dances, and your life might pass in a night. Names, debts, hospitality, music—all of these have binding force there.

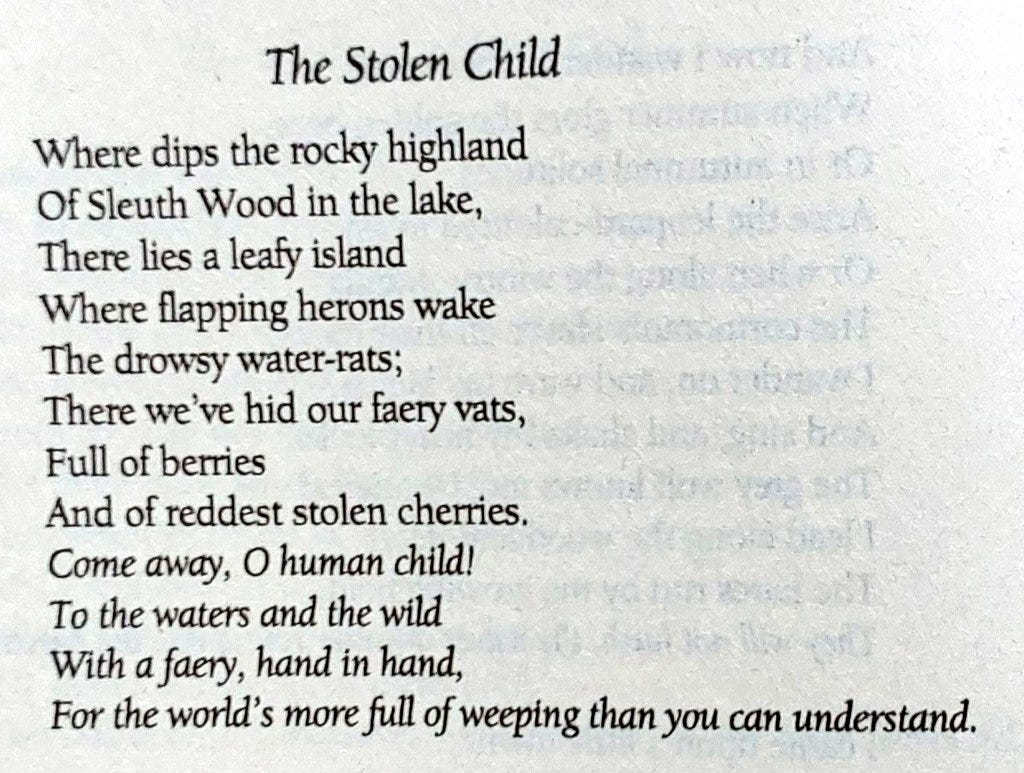

Here’s one of my favorite songs about this type of enchantment:

But William Allingham’s “The Fairies,” John Keats’ “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” and Christina Rossetti’s “The Goblin Market” also beautifully illustrate this theme.

The Victorian era sanded all of this down. It turned Fairyland into a gentle, miniature garden realm: child-sized wings, flower dresses, saccharine-sweetness. That version made fairies safe for nurseries and greeting cards, but it also stripped them of what made them interesting: their unpredictability, their alienness, their sovereignty.

The fairies of the folkloric traditions I pull from aren’t cute. Fairyland is an otherworldly territory that mirrors human fears and desires but refuses to play by human rules. It’s not a place of innocence.

And if you find yourself there, you haven’t entered a utopian fantasy—you’ve crossed a hedge, a border.

WE USED TO SEE THE INTERNET THIS WAY

We didn’t always treat the Internet like a bland utility. In the 1990s, many writers openly framed it in spiritual or metaphysical terms. Cultural theorists like William Indick and futurists like Mark Pesce compared the Internet to God. Some even believed it might replace God, just like certain prophets of AI insist today.

We also sensed, instinctively, that the Internet could separate body and soul.

In Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk: Cultures of Technological Embodiment, scholars described the archetypal computer nerd whose consciousness traveled through cyberspace while their physical body decayed in a chair. It’s a strangely mystical image for a supposedly rational technological discourse.

Yet despite these spiritual undertones, the dominant metaphor of that era (and ours!) became addiction. The Internet, commentators insisted, was like a drug.

But that never fully captured it. Internet use isn’t like snorting cocaine or drinking yourself to death—or even to injury.

It’s like stumbling into a fairy ring and getting stuck in Fairyland. You think you’ve been gone three days, but when you return—like Yeats’s “Stolen Child”—seven years have passed. You’re older than you realized. You can’t quite re-enter the human world. And for some people, the things they saw while they were away changed them forever.

THE DISENCHANTMENT OF CYBERSPACE

Today, discussions of the Internet’s spirituality have mostly vanished. We’ve replaced them with a utilitarian framing: the Internet as a tool, perhaps an addictive one, but nothing more.

And yet many people still feel—quietly, privately—that there is something deeply spiritual about being online.

My favorite examples are things like TikTok trends like “reality shifting,” where users claim they can slip between timelines. Or the meme-logic of “liminal spaces,” which gestures toward dreamscapes we don’t have language for. These phenomena suggest a primordial awareness that, like our ancestors, we’re accessing a realm beyond material reality, though we’re too embarrassed to say so outright.

Some argue the Internet seems “magical” only because people stopped understanding how computers work. The sociologist Sherry Turkle blames Apple’s smiley-faced icons and the invention of user-friendliness. By making computers intuitive, Apple obscured their mechanics, creating a layer of abstraction—and with abstraction comes mystique. Arthur C. Clarke’s adage comes to mind: any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

There’s truth in that, but it’s not the whole story.

Even with perfect transparency, cyberspace itself introduced new metaphysical dynamics.

For the first time, a person could be multiple selves at once. Turkle, who interviewed early Internet users in text-based Multi-User Dungeons, once recorded a participant asking:

“Why privilege the self that has the body when the selves that don’t have the body are able to have other kinds of experiences?”

Imagine that. The selves that don’t have the body. And this wasn’t a medium, psychic, occultist, witch, or LSD mystic—it was a normal person logging onto the early Internet.

What would a priest say if he heard that?

So let’s approach the Internet as if it’s a place. And not just any place—a strip mall or an office building—but an otherworld alongside our own.

Fairyland.

And how does one navigate Fairyland safely? Luckily, we have thousands of years of stories, myths, and warnings to guide us.

If you take only one thing from this essay, let it be this:

Fairies are real, and millions of people get trapped in Fairyland every day—just not in the way you thought.

RECOMMENDED READING

Robert Kirk, The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns & Fairies (1691 / pub. 1815)

Thomas Keightley, The Fairy Mythology (1828)

William Allingham, “The Fairies” (1850)

Christina Rossetti, “Goblin Market” (1862)

W.B. Yeats, The Celtic Twilight (1893)

W.Y. Evans-Wentz, The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries (1911)

Lewis Spence, The Fairy Tradition in Britain (1948)

Katharine Briggs, The Fairies in Tradition and Literature (1967)

Katharine Briggs, A Dictionary of Fairies / An Encyclopedia of Fairies (1976)

Brian Froud & Alan Lee, Faeries (1978)

Brian Froud, Good Faeries, Bad Faeries (1998)

Morgan Daimler, Fairies: A Guide to the Celtic Fairy Folk (2017)

One more reading recommendation: John Crowley, Little, Big; or The Fairies' Parliament. Magical novel from the early 80s.

Wonderful!!

My understanding of the perils of Fairyland is thanks to, among other sources, Susanna Clarke's wonderful period fantasy novel Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell. Highly recommended reading.