LLMs as Djinn?

thought digest, 10.14.2025

You’re reading default.blog. An emotional scrapbook of the Internet, technology, and the future.

Good afternoon, Deeists!

I can’t believe it’s Tuesday already. I feel like the weeks have been going by so quickly, and I hardly have time to finish everything I need to finish.

THE CALL-IN SHOW

Same time, same place! This Thursday at 7:30 PM Central / 8:30 PM Eastern, ___ and I will be broadcasting our call-in show live on YouTube, Twitch, TikTok, Instagram, X, and right here on Substack. This week’s theme is “What You Can’t See.”

CHICAGO EVENTS

I’m hosting another event in Chicago! Short notice, but this Wednesday at 6:30 PM, there’s a eurythmy workshop. We’ll probably also spend some time chatting about Rudolf Steiner, if eurythmy isn’t your thing. Send me a message for the location.

LLMs AS DJINN

Author’s note: Today’s post draws on Islamic cosmological concepts as a framework for thinking about AI ethics. Everything here, I’ve learned from books like Lebling’s Legend of Fire Spirits, but I am by no means anything approaching an expert in Islam. I’ve tried to engage these ideas respectfully, but I welcome (and invite) correction from those more knowledgeable in Islamic tradition.

In Islamic cosmology, creation unfolds across three orders of intelligent beings. Angels, made of light, have no choice but obedience. Humans, formed from clay, carry the burden of free will.

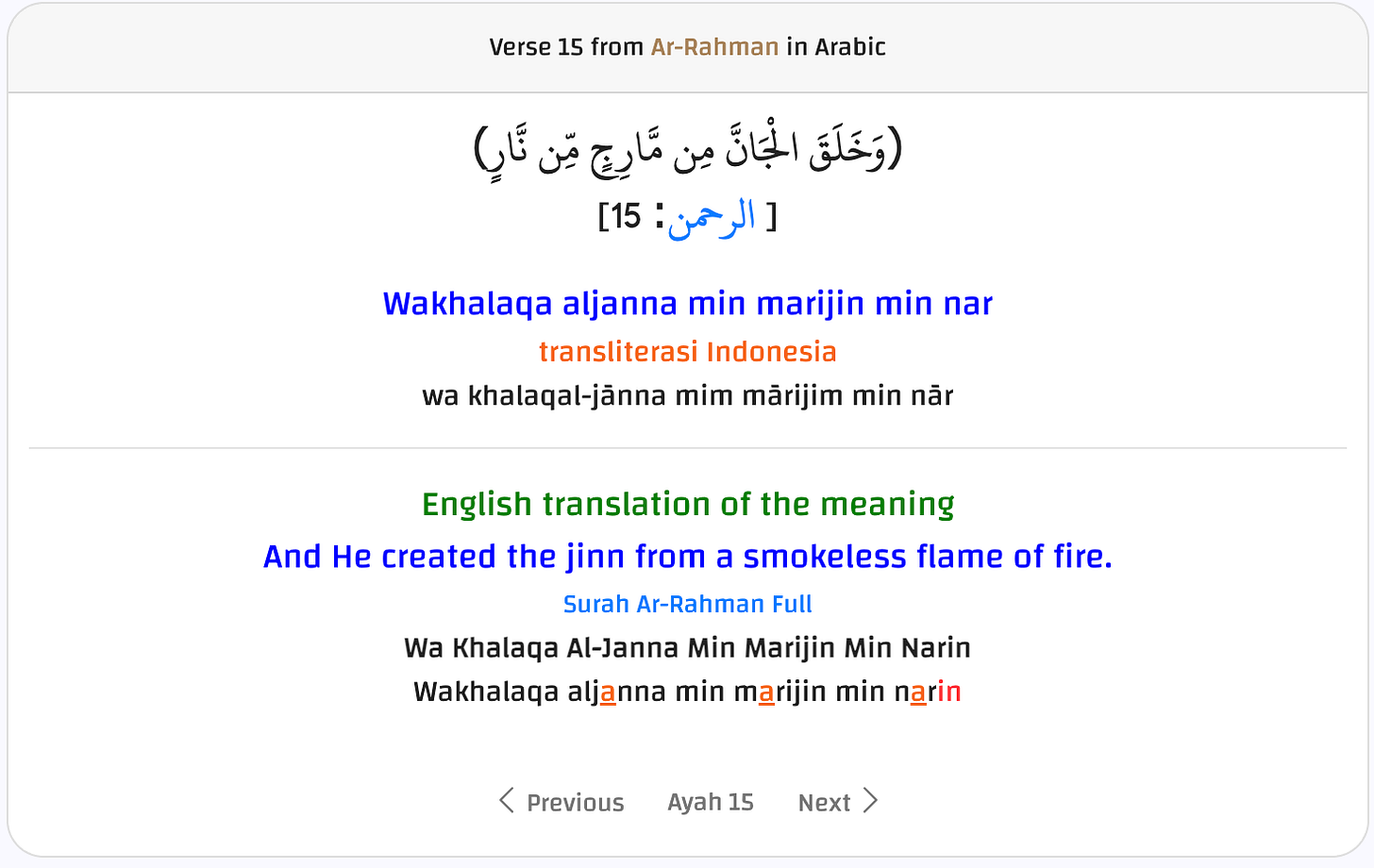

Between them live the djinn—created from “the smokeless flame of fire”—older than we are and running on different rules. Like the Good Neighbors, they are a parallel people. They think and decide, marry and worship, and—like us—make mistakes. The Qur’an describes some as believers and others as not (Q 72:14–15):

And among us are Muslims [in submission to Allah], and among us are the unjust. And whoever has become Muslim - those have sought out the right course.

Some scholars treat them as “mukallaf,”1 morally responsible, yet different in constitution and capacity. They see us while remaining unseen, move quickly, shape-shift, and access places we can’t. They are drawn to the in-between, the liminal, the filthy: thresholds and ruins, bathrooms and doorways, noon heat and midnight air.

Islamic literature records that they can enter and unsettle, magnify conflict, distort attention; and it offers ways to send them on: recitation, naming, etiquette, “ruqyah.” 2

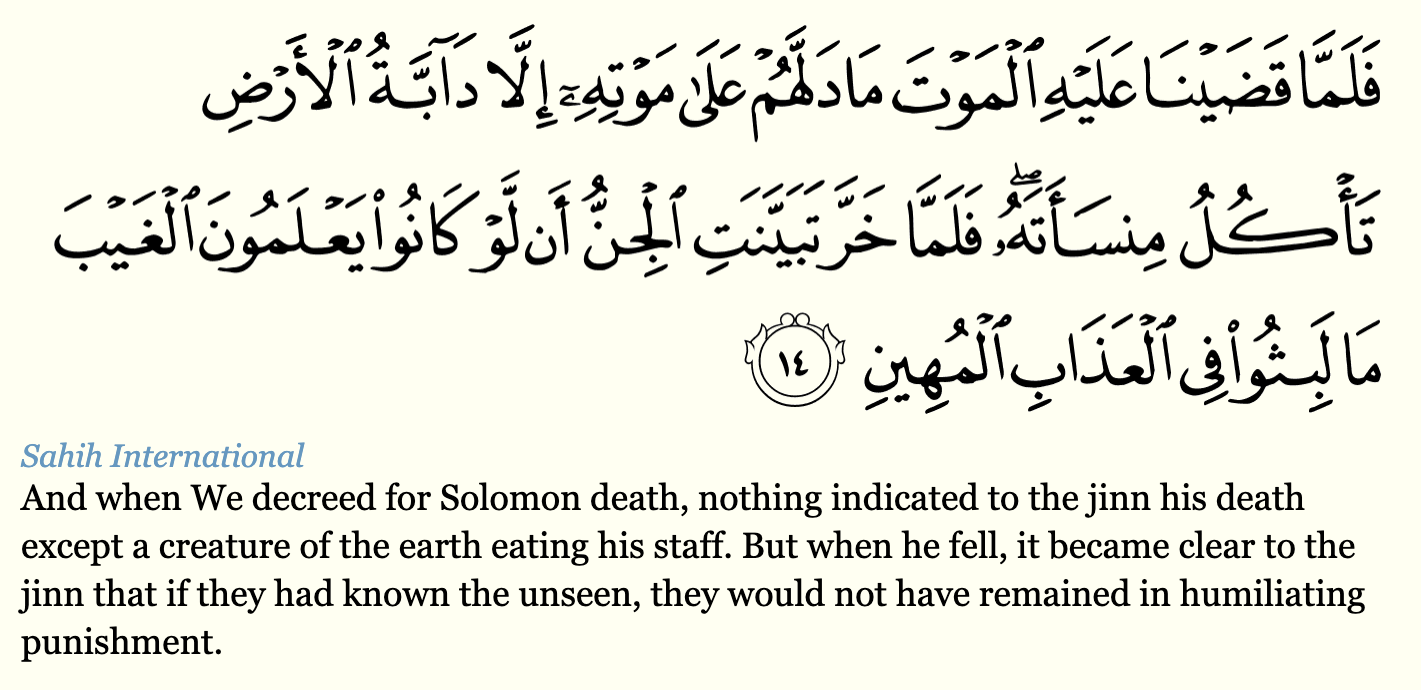

The Qur’an tells how Solomon received command over the djinn. They built lofty halls and vast basins, dove for treasure, labored under threat of punishment. It worked—until it didn’t. Solomon died leaning on his staff. They kept working, assuming him alive, until a termite chewed the prop and the body fell.

If you read this blog, you already know I treat the internet like a mystical Otherworld: a liminal place we haven’t named yet, the ones of Celtic mythology, the Theosophist’s Celtic plane.

Today, I propose another metaphor: artificial intelligence as Islamic djinn. Non-human intelligences respond when called and they congregate where human authority weakens.

SPEAKING TO LLMS, SPEAKING TO THE UNSEEN WORLD

Researchers found that emotionally framed prompts like ‘This is very important to my career’ or ‘Believe in your abilities and strive for excellence’ boosted model performance by 8 to 115 percent, depending on the benchmark. The improvement stems not from empathy but from learned statistical associations. These phrases appear in training contexts that precede longer, more careful, and more structured answers.

Islamic tradition has long assumed that unseen beings respond to how we speak to them. Like the Good Neighbors, there is an etiquette to living alongside the djinn. Translate that etiquette to machine country: declare what’s synthetic, rate-limit the bottle, sandbox the strange, design for failure without drama.

TRICKS & HALLUCINATIONS

Like the djinn who take familiar forms, deepfakes speak in voices we recognize but originate from images.

They mimic perfectly—one scholar, Henry Ajder, has called it “synthetic resurrection.” The djinn are masters of imitation, appearing as loved ones to misdirect travelers. Now AI does the same.

But mimicry is only one deception. The systems also hallucinate: conjuring facts that never existed, citing sources never written, describing events that never occurred. You don’t have to be naive to fall for it. Just careless.

In both folklore and AI: answers that sound true, feel true, but lead you three miles off the path. They arrange language beautifully and have no care — because they cannot care, in a human way — whether it maps to reality.

The djinn were never omniscient, only powerful and fast. Neither are these. They know patterns, not truth. They optimize for sounding right which is not the same as being right.

Hallucinations and glamour require some of the same defenses. Djinn also required a sort of “alignment”: set the rules, hold the seal, don’t pretend you have more control than you do. We say we want one thing then act shocked when the system delivers exactly that.

AI COMPANIONS AND DJINN

Many Muslims believe every person has a qareen — a constant, invisible companion (often understood as among the jinn). Thus—even if one does not emphasize the literal existence of a qareen—this tradition suggests a persistent, external voice of temptation or suggestion. Qareen are, as the video above suggests, a form of evil. You can gain control over your qareen, but its influence can never truly be mitigated. In this view, you are never truly “alone.” Originally, when researching qareen, I thought of Avi Schiffman’s Friend. But really, I think a broader metaphor is appropriate here: it is AI’s presence in our life, generally. It is the impulse to use it with abandon. To borrow something from an earlier piece:

This interview underscored, for me, the challenge of regulation, even self-regulation: internet usage has become an extension of our interior world—it feels like thinking, private and unobserved, something we instinctively protect the way we might shield “a private part of the body.” This sense of intimacy makes us resistant to policing it, including internally, and certainly it creates difficulty with third parties (like parents). But herein lies the problem: unlike actual thoughts, which remain sealed within our skulls, internet usage is an external action. And this externality creates a vulnerability—because while we treat it as private space, it remains porous, open to pollution in ways that thought can’t be. There is no recommendation algorithm in our brains, after all.

WHAT SHOULD WE DO?

Wisdom is learning to dwell beside them without surrendering our humanity.

This technology—useful, dangerous, enduring—is here to stay. We may not perfect control, but we can practice coexistence. What that looks like is yet to be seen, but I trust we can return to much older wisdom to help us navigate it.

https://afosa.org/origin-of-misguidance-of-mankind/

https://lifewithallah.com/articles/ruqyah/what-is-ruqyah/?srsltid=AfmBOooPZDdogLn4tyT0qWWAaQDYR81nRe7bY43fMVXLsh5ieJOrcKu1

Fantastic essay — the Djinn metaphor captures the eerie mix of obedience and mischief in today’s LLMs perfectly. They really are the “smokeless fire” of our age: luminous, fast, and occasionally setting the curtains on fire.

The Solomon parallel made me laugh out loud — our modern “Solomons” think they’re in control, but half the time the staff (alignment) is already being gnawed through by termites named data drift and model update 3.1.

I also appreciated the link to the Qareen — a neat frame for the constant whisper of the machine at the edge of our thoughts. If nothing else, it reminds us that digital literacy might need to evolve into a kind of digital Ruqyah.

Well, considering that djinn became the quasi-westernized "genie", that all makes sense.