Digital Places, Lucid Dreaming, and Camgirls

thought digest, 09.10.2025

You’re reading default.blog. An emotional scrapbook of the Internet, technology, and the future.

Good afternoon, Deeists.

Sorry for my absence – I’ve been sick! Here’s this week’s thought digest — a round-up of stray thoughts, links, and what I’ve been up to.

TOMORROW’S CALL-IN SHOW

Tomorrow’s call-in show theme is LUCID DREAMING. As always, you can tune in here, Twitch, YouTube, or X.

WORLD-BUILDING

I’ve been thinking about how brilliantly camgirls — not e-girls, but camgirls — world-built. Reading Theresa Senft’s oddly underappreciated (and mysteriously poorly reviewed) ethnography of pre-2008 camming, I kept returning to this idea: the internet used to be full of actual worlds, and now it’s mostly not.

When you landed on an early camgirl’s site, you weren’t just watching a performance — you were entering someone’s bedroom — their stuffed animals, their messy desk, their cat wandering through frame. Between shows, they’d blog about fights with their roommates, their favorite TV shows, how they were feeling. There was a real sense of interiority, even if the content wasn’t highbrow. Viewers became invested not just in the sexual content but in the ongoing story of their lives. They built complete universes without knowing who would enter them.

This same quality existed across the old internet. LiveJournals, MySpace profiles, personal homepages, early YouTube channels — these felt like stepping into someone’s actual room. There was a sense of place.

You can still find this occasionally. Certain Substack writers create it — my friend Tara Isabella Burton’s blog smells like a vintage velvet dress. But this feeling is increasingly rare. Most online writing, even very good writing, feels like it comes from nowhere in particular.

It’s trying to say something — and often succeeds — but it’s not taking you somewhere.

The usual explanation for this shift is that interfaces used to be customizable — you could pick your MySpace background, arrange your LiveJournal layout. But I don’t think it’s about customization. I think it’s about the difference between sharing your life as a world others can inhabit versus the economy of takes, products, and lifestyles.

Camgirls were selling themselves — or rather, carefully constructed versions of themselves — and then waited to see who would be drawn in. They didn’t know their audience yet. The seduction wasn’t just sexual — it was about making people invested in an ongoing narrative, in who they were when the camera was off.

I’ve been conducting ethnographic interviews about online life for a few years now, and this shift comes up constantly. People describe how the “old way” of being online was generative: you built your world and discovered who it attracted. You found others on the planet you thought you lived on alone. The new way is more extractive — you identify a market first, then craft a persona to match it. It’s not necessarily worse, but it is different.

This world-building still happens in pockets, though. Early TikTok had it — that feeling of stumbling into someone’s weird, specific life. I once bought pistachio milk because I became fascinated by a single mother who was constantly drinking it on camera. Not because she was trying to sell it to me, but because something about this window into her life — the cluttered kitchen, the kids’ voices off-screen, the way she talked to herself while cooking — was interesting to me.

She made me curious about things I wouldn’t have otherwise been curious about and I wanted to try living in her world for a moment.

I’d like more of that online.

LING FROM STRIPE REIMAGINES FILE BROWSERS

Ling, a product designer at Stripe, recently tweeted:

my gripe with all digital file management is theres no sense of spatial memory when i studied for tests i remembered the shape and structure of my notes and that pointed me to where things were (see memory palace) modern file systems feel like a magic soup where you whisper your best guess at the name into the void someone please fix this

Then later, she posted this:

I prefer to view my files as lists but I really like the spirit of the idea.

DF IRL

I have quite a few events coming up:

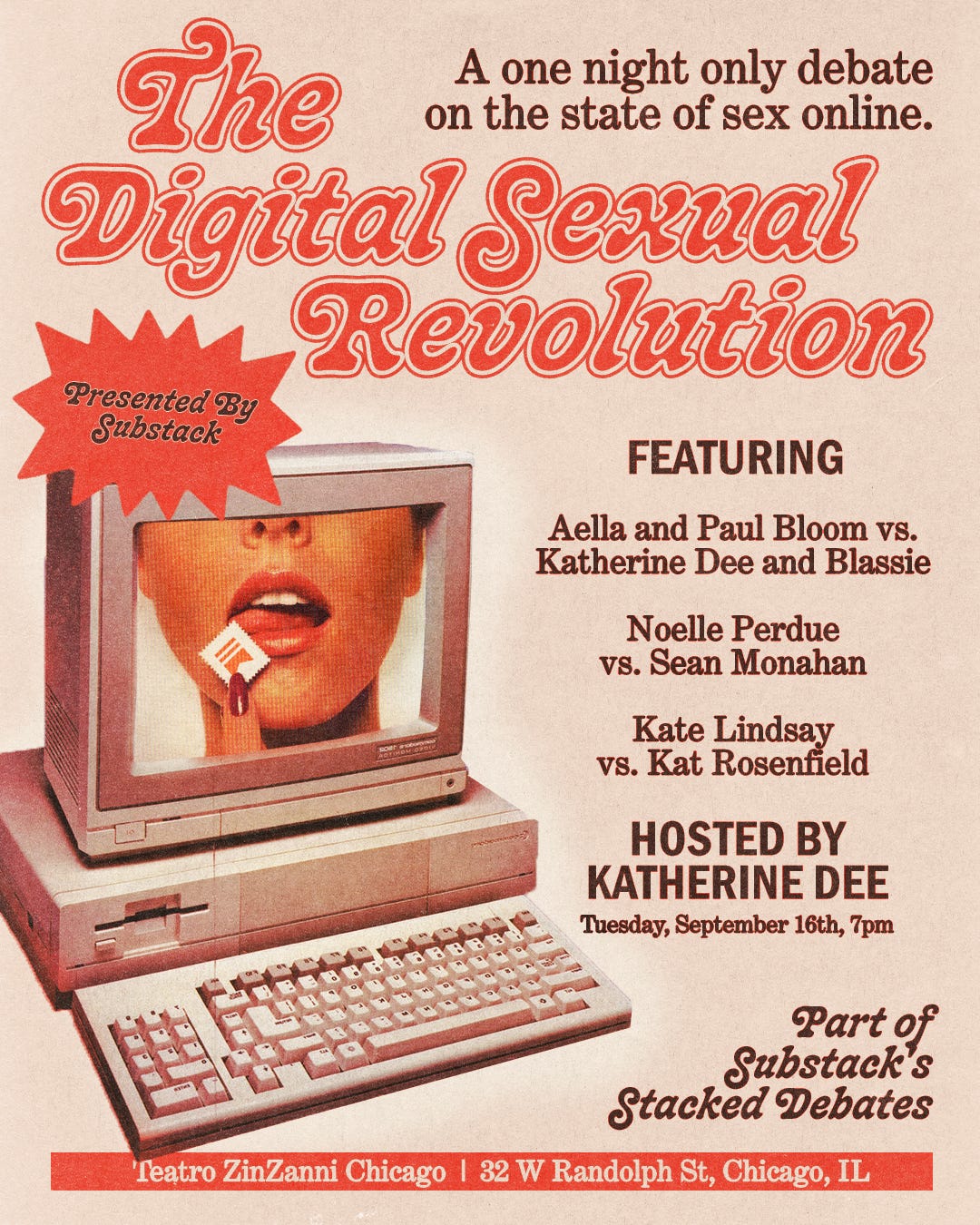

On 9/16, I’ll be debating Aella and Paul Bloom alongside blassie about whether sexuality is innate or influenced by the Internet. You can grab a (free!) ticket here.

I’ll be in the Bay Area 9/18-21, and quite possibly that following weekend.

On 9/24, Leigh Stein and I discuss her new book, If You’re Seeing This, It’s Meant For You. Grab another free ticket here.

ICYMI

Jean Pormanove death exposes dark heart of streaming for UnHerd

Robin Westman and the unstoppable tide of ‘slop violence’ for The Spectator

MY FRIEND, THE CAMGIRL

I.

Swan broadcast from a one-bedroom apartment off I-35. Behind her: a head shop tapestry, thumbtacked directly into the drywall. To her left, just out of view: a mountain of laundry that migrated between bed and floor but never made it to the closet. The camera saw only what she allowed—her torso, her altar with its chime candles, a fish tank filled with water and algae but no fish.

She’d play entire Evanescence albums while she worked, always in the order Amy Lee intended. Men would tip her to change the song, but she never did.

“This is my space,” she’d tell them. “You’re just visiting.”

This was pre-Covid, pre-OnlyFans, back when cam sites still felt like collections of rooms you could walk between, each with its own temperature, its own rules about how time moved. MyFreeCams, Chaturbate, LiveJasmin—these were places, not platforms. Swan understood something fundamental about this architecture: what made her camming compelling wasn’t the pornography but the world she constructed. Men paid just to exist in her space, to watch her arrange her perfume bottles, to feel like they’d been admitted somewhere secret.

Swan was four-foot-eleven and proud of it. Men thought she was a child, she’d tell anyone who’d listen, not like a teenager, not like sixteen, but an actual child, like eleven, twelve. She had this story about how she’d been walking home from the pool one day, and a guy stopped in his pick-up truck, shouting something at her, and somehow, it dawned on her that he thought she was a little girl. Her hair was this Crystal Gale situation; went past her ass, somehow still growing, always electric with static and over-brushing, stringy at the ends. She protected her “young face” with sun hats and thick white sunscreen, even in winter, even at night.

II.

I met Swan at a Starbucks. She was in full goth regalia, reading Tarot cards. She was a swan, she told me. And I was a dragonfly, though I never took it as a name. Her husband Evan was there too—tall, quiet, worked at Party City surrounding himself with carcinogenic costumes and cheap glitter. They’d met in high school, two people who believed they were “of the fae,” or had faery blood, and built a marriage around this shared mythology.

After our full moon rituals — we’d do spells by the lake every full moon — Evan would drive us to the Walmart on Ben White, the one that stayed open twenty-four hours. Swan and I would abandon our shoes in his car and run through the automatic doors barefoot, our soles black by the end of the night. We’d tear through the aisles, opening boxes of Cosmic Brownies, pretending to be drunker than we were from the Barefoot Moscato we’d shared.

Evan followed ten feet behind, holding our shoes like evidence, apologizing to no one.