The Internet Is the Astral Plane. It's Getting Dangerous.

+ stalking, stans, theosophy, and violence

You’re reading default.blog. An emotional scrapbook of the Internet, technology, and the future.

Hello, Deeists!

I’m still working out how to balance free vs. paid newsletters… and, frankly, how to get these out on a schedule that actually makes sense. But I digress.

Yesterday we held our second Chicago event, celebrating the wonderful Leigh Stein at one of my favorite venues in the city. Our first two events — the Digital Sexual Revolution Debate and last night’s panel — both had great turnouts. Now that we’re venue-rich instead of venue-poor, I’d like to bring back the in-person book and writing clubs we had running for a while. There’s also a eurythmy class and a Rudolf Steiner study group in the works.

A lot going on up here in the Midwest! I will keep you all abreast of the schedule.

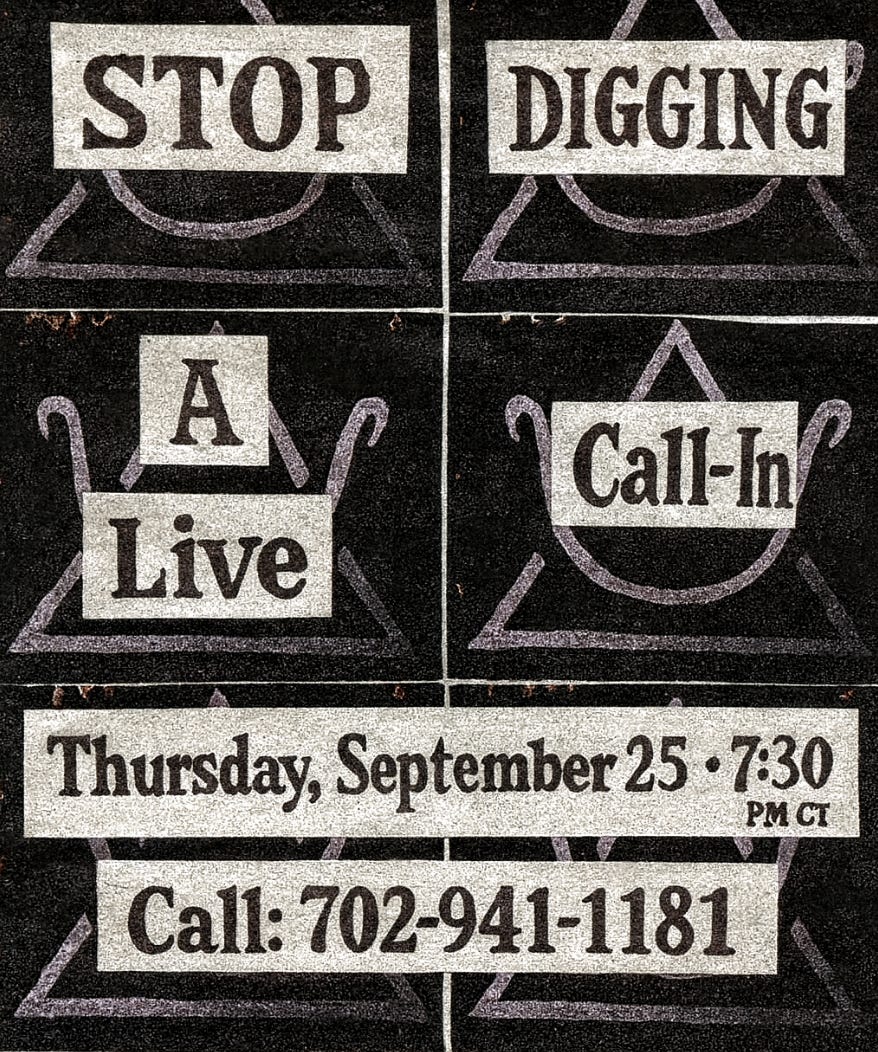

Tonight’s call-in show is at 7:30 p.m. Central, as always. If you’re new here, every Thursday I host a call-in show, a kind of homage to Art Bell. Each week I pick a theme that can be read two ways — either about the paranormal or internet culture. This week’s theme: STOP DIGGING.

We stream on here, X, Twitch, and YouTube.

Since many of you are new, here’s a quick rundown of this week’s writing and events.

This week I published two pieces at The Spectator. One was about witchcraft — framed around Jezebel’s stunt of hexing Charlie Kirk. I wrote it partly in response to Megyn Kelly’s monologue about the dangers of witchcraft:

The gist is she sees witchcraft as not only real, but dangerous. A lot of people I respect scoffed at this — and even though I myself also believe in witchcraft, I did too, initially. My logic was, “Well, not all witchcraft is created equally.” Even among occultists (and people who believe in the occult but don’t practice), some stuff really is just for entertainment or is otherwise powerless. Etsy witchcraft tends to be up there — it’s not real believers who are buying those spells, it’s mostly desperate tourists to the magical arts.

But the more I sat with it, the more I could see Kelly’s point, even if I still didn’t agree with her premise literally.

My argument is that we’re all already participating in a kind of “accidental witchcraft” every time we post online, directing energy, attention, and malice into a space that can spill back into real life. That is, even if the hex wasn’t real in the sense that demons were actually attacking Charlie Kirk — what is real is the focused hostility that go into hexes, and that can create real-world action.

The other piece was about nihilism. The Internet has become an incubator for three different kinds of threats simultaneously. I think these three distinct threats coexisting is really muddying our analysis.

There are people who believe life is suffering, so they must act with violence.

There are people who believe life is meaningless, and thus act with what I described as “slop violence” in an August 29 piece.

There are the “revolutionary normies”: ordinary people with jobs, friends, and families, who nevertheless come to believe that only extreme spectacle can break through the noise during what they see as true moral emergencies, themselves the product of hyperbolic media.

Taken together — both witchcraft and emergent violent threats — these ideas are part of a larger theory I’ve been developing: that the internet is our Fairyland, or even more saliently, our astral plane.

Like the astral plane described in Theosophy, the internet is a parallel dimension layered over our reality. It’s a place where thoughts take on form, distortions masquerade as truths, and some people return damaged from staying too long. It’s not just a metaphor; it’s a way to understand why online life feels haunted, why attention itself has power, and why the stakes of digital culture so often spill over into physical life.

I’ve had a big subscriber bump this month. To nudge more of you onto the paid side, here’s a coupon:

THE RISE OF THE STALKER FAN by Monia Ali

While ‘stan’ has become common parlance to describe yourself and other zealous fans, it doesn’t have much in common with the original Stan, the fictional violent criminal that Eminem sang about. Stan represents the potential worst-case scenario of having a psychotic fan latching on and spinning out of control.

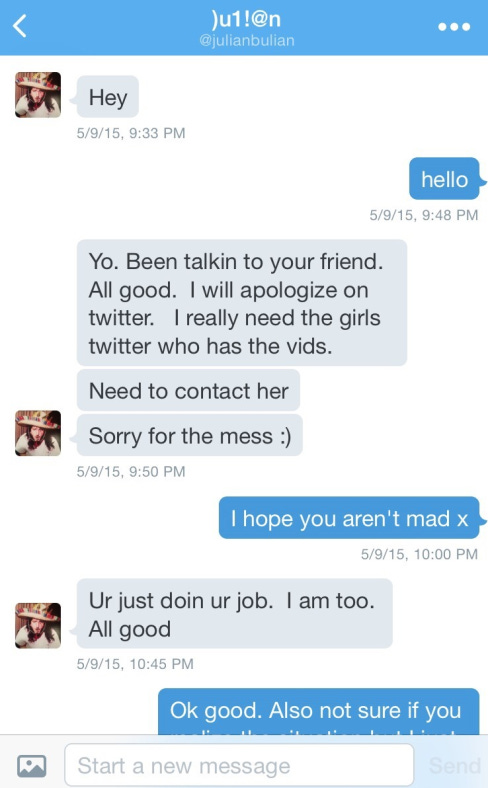

That isn’t to say that there aren’t stalkers present within fandom and self-identified stans; nor am I suggesting that violent stalkers aren’t an issue, but rather that they typically inhabit a different sphere from fandom. The stan tier of stalking is of a different type; it’s one where the relationship between fan and fan object are still acknowledged.

It’s also about entitlement, since collecting and absorbing information has been normalized in fandoms over the years. Because of this, much unscrupulously obtained data is unavoidable once it gets online; the glut of available information that gets compiled begets the desire for more.

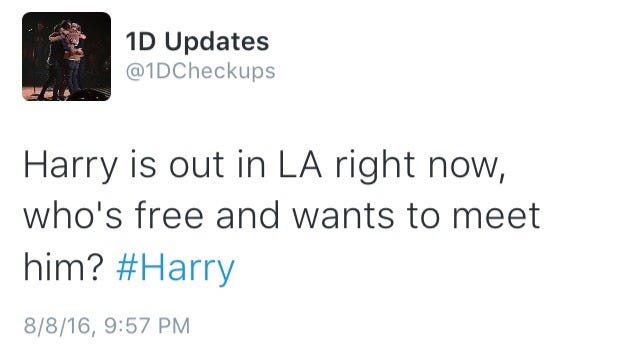

This desire can be manifested into cyberstalking; another fandom issue that has spread far beyond the 1D sphere, as journalists are now becoming targets of harassment campaigns. Digging up LinkedIn profiles, spamming employers and families and anyone, really, that crosses a line, has been a long time in the making.

As Brodie Lancaster wrote about the blurring of the lines and the illusion of intimacy, “You can’t tell where the lines are until they’re crossed.”

The line was far behind us by the time I was told about investigations intrusive fans had participated in. They had run the gamut, from hacking into travel emails, IRS and Facebook accounts to obtaining CCTV loggers from hotels and airports; tracking frequent flyer numbers, and hotel stays and properties. From leaking the passport photos of an employee’s daughter to gaining access to close friends and families’ private Facebook accounts.

These are the same fans who object to invasive interviewers and disrespectful journalists, despite their own breaches. Whether that’s a stalking guide or inquiring about the band members’ circumcision status.

I suspect part of the doublethink on behalf of the fans, in this case, is because they see themselves as occupying another sphere from their fan objects. The instinct of online fandom isn’t to be seen, it’s to observe and experience by proxy. They don’t seek to advertise what they discover, not beyond closed groups of people who are considered “deserving.” Plus, they don’t intend for it to be known that they’re doing things like this.

Another reason why the cyberstalkers believe themselves to be different is because of the abundance of stalker fans, “insiders” and others aided and supported by official sources. Contests are rigged in their favour—sometimes, they’ll receive the prizes without making an effort—they’re rewarded with “unseens” and unpublished paparazzi photos and candids; sometimes, they even attend birthday parties of tangential players.

January 2016 is when Jeffrey Azoff, Harry Styles’s longtime manager, celebrated his birthday at the Troubadour in Los Angeles. Why do I know this? Because The Insiders took video and photos, reporting live on minutia as if the industry-heavy party was relevant to 1D fans.

There was no reason for me to find out about this event, yet it was presented as pertinent. For me, this was an early glimpse behind the curtain, as to how focus could easily be directed, and how access and information were meted out for convenience.

One of the members of the so-called London Stalker Crew (whose tweet is embedded above) admitted in an interview that the run-ins were not organic,

“So it’s not like a coincidence; we just know they’re going to be there, even though there is a lot of trials and errors at trying to find them.”

Often enough, the information came from bodyguards, sometimes the entourage or hangers-on. Occasionally, it is illicitly obtained. In fact, it’s encouraged when you’re part of certain groups.

Being an insider for an update account is a good way to rack up meetings/selfies/run-ins with your idol of choice, and most of the insiders who’ve become characters of their own have had affiliations with such accounts.

One of these is Stalker Sarah, whose coverage includes a magazine spread and a New York Times editorial. She has shared occasions that she’s been called, one being the time the team behind the band The Wanted got in touch with her and “requested that she help give them the welcome they deserved by getting her followers to the airport.”

Sometimes mobs are orchestrated in such ways; sometimes, even though they are, things get out of hand. But a mob looks good on camera and serves to stoke maximum interest.

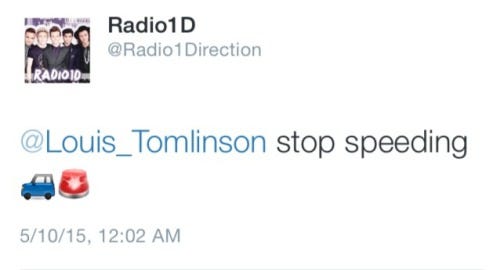

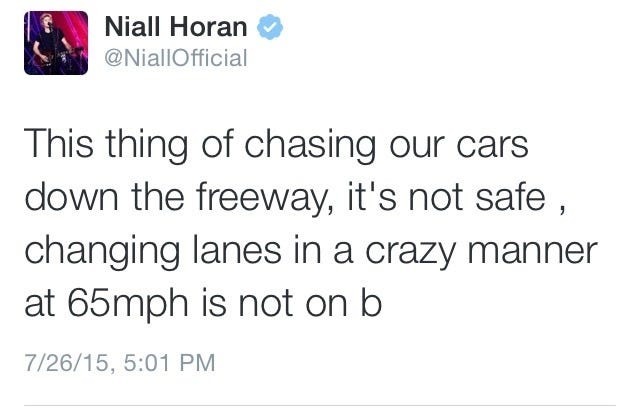

Sometimes car chases happen; throngs of fans running in traffic, trying to catch up with cars trying to abide by traffic laws.

There’s never a complete match between what is given to insiders and fans and what they want, which is how egregious breaches take place. A slew of them took place on the same day in Australia in 2013. 1D was there on tour, Liam Payne and Louis Tomlinson went surfing and caught a less than respectful crowd, resulting in Tomlinson being groped.

At the hotel, fans approached Payne’s room, and a pair of insiders managed to steal his underwear and other knick-knacks from an adjoining room. Both events were captured by paparazzi, with dystopian shots of fans climbing up the exterior of the hotel, but neither lead to any repercussions.

Despite all the information given to insiders to pass on to the fandom,it happens that they get it hilariously wrong. Whether they’re purposefully misdirected or digging up incorrect information, it is a stark reminder that these insiders and accounts are nothing but intermediaries serving a purpose.

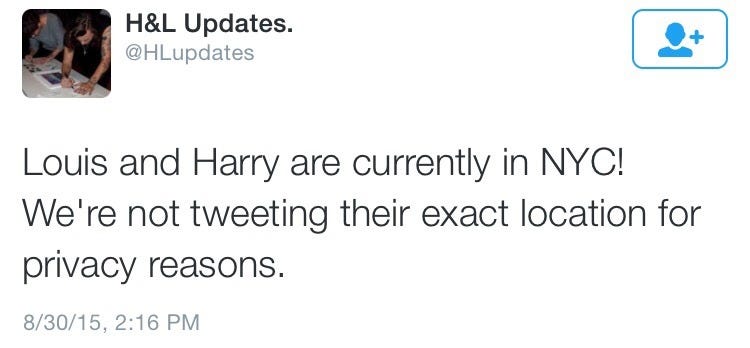

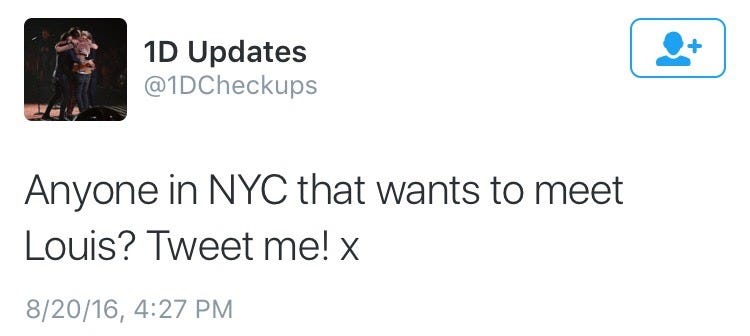

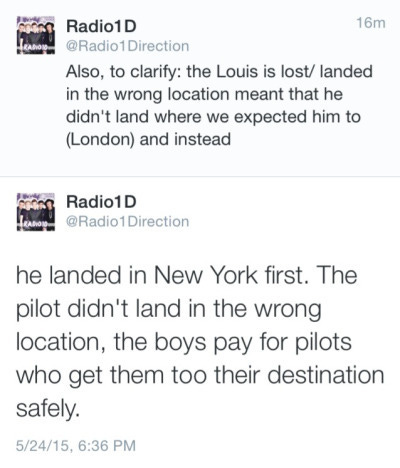

One of the classic mistakes involves flight tracking; Louis Tomlinson was reported as being en route to Europe, but the plane landed in NYC. Instead of realizing that perhaps he was on his way to New York from the get-go, the account doubled down hilariously:

Jordyn, who was featured in Teen Vogue made her name by sharing information for fans to meet the band via a now-suspended Twitter account. According to her, “fans had to resort to meeting the band on their own,” once meet and greet tickets became harder to score. In the years since she entered the scene, she’s accumulated bylines from the Daily Mail and The Sun, participating in the very tabloid game that fans normally scoff at.

The stalker fan known as Boopsy was also featured in Teen Vogue’s article as an insider with clout. She was an early tracker of flights and hotel stays. She told them, “It was so empowering knowing that I was the only one who had the information.”

Despite the continued sketchy behaviour, it’s inevitable that those that provide new content and new information will gain status. Because of this, all criticism of their antics is framed as jealousy. It’s easy to pull the jealousy card, and I daresay that some are jealous of the preferential treatment they receive in contests. Stalking being rewarded with the meet and greet opportunities, special gig invites, limited exclusive merch isn’t really the way to make it stop. Then again, it doesn’t seem like stopping it is on the agenda.

I don’t think pointing out that playing in traffic is unwise is a sign of jealousy. I don’t think the scenario outlined in the tweet below, featuring Jordyn, is anyone’s dream encounter.

When it comes to Boopsy, a lot of hostility comes from the belief that Styles has taken out a restraining order against her. I’m not sure where the rumour comes from, aside from fans projecting their own wishes of stalkers being left out in the cold and finally facing consequences.

I couldn’t find much evidence of a restraining order being in place, and I do think it would be fairly easy to confirm. For one, Styles currently is dealing with a once convicted stalker who has continued to escalate. Notably, in this case, there appears to be no connection to fandom, either as a catalyst or introduction. Boopsy even wrote about the case for a gossip outlet, something I don’t think she would be permitted to do without repercussions were the rumours accurate.

Additionally, Styles has been granted a permanent injuction against “Paparazzi AAA & Others.” This precludes pursuit, observance, photography, loitering, and tracking of his movements. Considering his proactive shutting down of unwanted attention, it seems unlikely that any disturbance would be tolerated for long. This is also relevant considering the amount of paparazzi photos of him are taken. He is very capable of shutting down unwanted attention. He’s also very capable of staging his own shoots, and does so frequently.

While all these examples are rooted in 1D fandom, none of this behaviour is exclusive to that fandom. At some point, insiders and stalker fans became a piece of fan management pie. Just like the shippers being used to drum up hype (explored in detail in my participatory culture post).

The only real backlash I can think of was the time Demi Lovato went on a tirade against Stalker Sarah on Instagram. She even made sure to say her family was not afraid to press charges, something that didn’t happen. Instead, Sarah framed the comments as a malicious hack, and remains on the scene, and the stalking carries on.

Somehow, for some reason, keeping these stalker fans on deck and at the ready is worth it to whoever calls the shots.

![[animate output image] [animate output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!9ORU!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F01e6dab8-60bb-40ac-902b-7bb3a19b33d8_245x184.gif)

"Stop digging" feels directed at me, specifically... 👀 I have so many thoughts on that!

I agree with your general idea that what media does is essentially magick. These are the tools that shape our reality. And I know you’re not blaming the Etsy witches here. But, if we’re going to look at this through a magickal lens, I think it’s important to also point out that before his death, Kirk was also doing exactly the kind of magick that you describe, and on a much more powerful scale.

His whole schtick inititally was utilizing the medium of the internet to harness rage and stoke divisiveness in exchange for attention, and then focus those energies towards his own agenda. What he was doing was much more powerful magick than anything you can buy from someone on Etsy.