Why Does Being a "Hot Girl" Have Nothing To Do With Sex? Plus Sissy Hypno and Farming Out Our Intuition to Mystics

thought digest, 07.19.2022

I’m back from my crazy two months of traveling.

Well—sort of—I have one more trip. During this trip, I’ll have more control over how I’m spending my days, and I’ll have internet access, two things which have been inconsistently available to me lately. This means more writing, not only here but elsewhere, too.

I’ve been brainstorming how to provide more value to paid subscribers, and I think I’ll try to offer more long-form pieces and paywalling half of the thought digests, which will now be weekly instead of our usual schedule of “whenever I feel inspired.”

I know this newsletter is constantly evolving, and I’m thankful for everyone who’s stayed with me through it all. As an aside, I recently crossed a significant subscriber milestone, so thank you for that, too.

You asked (more times than I’m comfortable with, frankly)—I answered. I’m diving into the world of sissy hypno. If that’s a phrase that’s new to you, sissy hypnosis videos are a form of erotic hypnosis that promises to “transform” the viewer into a “sissy,” a biological man who performs a hyperbolically eroticized female character. Sissy hypno falls under the broader umbrella of forced feminization, which is part of the even more sweeping genre of transformation pornography. Coincidentally, both are also frequent themes found in fan art, and have wormed their way into mainstream culture via fandom.

My instinct is that this isn’t a weeklong or even month-long anthropological expedition into a discrete digital community or pornographic genre. I think to understand sissy hypno and to offer any worthwhile insights; it’ll require months of work. Right now, I’m surveying the ground: the histories of BDSM and hypnosis, especially erotic hypnosis, pornography, and crossdressing, to name just a few areas of research.

I’m reading Torrey Peters’ novella The Masker to kick off my journey—I’m about halfway finished as of writing.

Early in the book, our protagonist, a crossdresser, meets a married Argentinian man with an affinity for transgender women. Here’s a passage that stuck out to me…

“He tells me that I’d make a good wife, that I’m funny, that I cast my eyes down shyly when I laugh. The idea of myself as a wife, of belonging to a man like this, makes me feel demure, vulnerable, and turned on. I’m suddenly very aware of my nipples.

“I want to take you shopping tomorrow,” he proposes, then holds up a hand, as though I’m about to interrupt when already I’m nodding enthusiastically. “I know, it’s very Pretty Woman. But one of the fun things about girls like you is how excited you get over clothes. My wife, she doesn’t like to dress up for me like that. I love shopping with the girls I meet here.”

I squeeze his hand in a yes. This is why I’ve spent so many cold Iowa nights under the covers touching myself: my online sissy fantasy Daddy come to life.”

My kneejerk reaction to this was a question, “Is this part and parcel of learning about certain experiences from media representations, as opposed to experiences, direct observation, or even stories from friends and family?” What happens when most of what a society knows about other people comes from television, movies, and the Internet, instead of the physical world?

Something else guiding my thinking, at least today, is a quote from Dr. Gloria Brame, a sex therapist who specializes in BDSM. In an interview on the podcast Evolve Your Intimacy, Dr. Brame says that one feature that distinguishes BDSM as an alternative sexuality is that it’s not tied to physical arousal. Physical arousal may happen in a BDSM scene, but in her understanding, the participant’s psychological experience is always foregrounded.

I’ve written before about how the Internet conditions people to separate the mind from the body. It also seems to do a good job of separating sexuality from intimacy, and at its most extreme, from desire itself. This, of course, adds some interesting color to Dr. Brame’s perspective—did BDSM spread in online fan spaces (and among the geeky fringes more generally), because of how cerebral it is? It’s not just the pedantry of rule-making and careful planning, it’s something deeper in the practice itself.

Drag Queen Story Hour. I’m about a million years late on the Discourse, but while we’re on the topic of cross-dressing, one thing I kept returning to when people were at the height of arguing about drag queens was, “What’s the role of the storyteller in modern America?”

To my mind, liberals see drag queens not as sexual performers but instead, closer to a court jester. You know, someone approximating Disney’s Clopin, the jester who relays the story of the Hunchback of Notre Dame to the audience through song, dance, and puppetry.

My encounters with whimsy and theatricality came through TV, like most millennials, but also, I grew up in a place and time where in-person variety shows, hired character actors at birthday parties and local libraries, and family traditions like male family members dressing up as Santa Clause, were still relatively common. I think all these examples serve the same function as Drag Queen Story Hours: kids love expressiveness.

So I started to wonder, does this role—this storyteller or jester role—still exist in ordinary American life? I have no idea. But I’ve noticed a more significant trend of sexual identity being abstracted from sex and neutralized for general consumption to fill a gap left by atomization, so something tells me it might have disappeared.

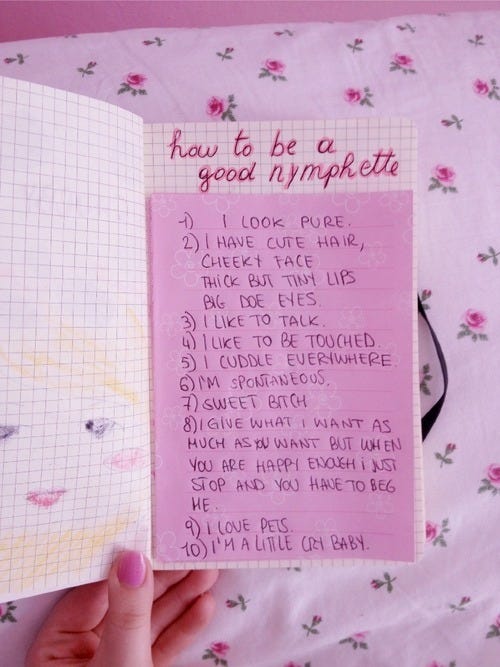

A history of Tumblr nymphets. Last week, I wrote a response to Roisin Lanigan’s June i-D piece about femcels. Lanigan received a lot of backlash for her femcel article, at least in the corners of the Internet I occupy. I want to give credit where credit is due, though—she wasn’t pulling a movement out of thin air. She was recognizing something real, but misidentifying the name, she was also obscuring this group’s origin: the Tumblr nymphet. I did my best to trace the lineage. You can read the whole piece here.

Indian Bronson on journalism. I know it may seem like I’m not unnecessarily but maybe disproportionately critical of the press. I want people to trust journalists more, because there’s a lot of good journalism that gets overshadowed by the shitty politics that infect the entire industry. After an uncomfortable run-in with Mother Jones, Indian Bronson had this to say:

“Journalism isn’t about keeping people informed, or seeking the truth. No. It’s about making people with something to lose fear they’re next if they don’t think, act, and behave exactly as the favored political and media incumbents of the US elite classes want them to behave, or at least fear the social embarrassment that will oh-so-certainly be caused to befall them when it’s revealed they believe in gauche things like arithmetic or not lying about crime.

I’m not totally sure what motivates one like Noah Lanard to feel so compelled to serve this kind of agenda. […]Journalists, though, who put them in charge? What drives them? They want to police the bounds of our democracy, but did we ever elect them? Why are their opinions more important than anyone else’s?”

Because, dear Bronson, most people don’t have time to learn about the world around them—to build a story to help navigate the world. So, storytelling becomes a career path (and a necessary one!) to help everyone else navigate life, and thus we have the Journalist. But, of course, capital of any kind corrupts: social, financial, sexual.

What drives them, you ask? First, they probably want to tell the truth. They like to write. But then they want to be influential; they want to be on the right side of history; they want to be in the ‘in-crowd.’ Storytellers have a real chance at having the type of legacy not many of us do and when you’re at a publication of a certain size, you’re validated by titans of industry, celebrities, large readerships, the very wealthy, it girls. Even people who outwardly hate you will still invite you to things. You still get special access. I get it. It’s hard on us, the readers; it’s also hard on the journalist, many of whom neither achieve influence nor an outlet for writing that keeps its integrity.

The solace I can offer you is this: while I don’t always agree with the story about the world that you yourself are telling, you have a following. You’ve found your like minds. And because of that, you stand a real chance at leaving a mark, too.

Other recent articles by me…

Also for RETURN, I interviewed Emmet Penney about his nuclear advocacy work, Alex Kaschuta about her podcast and writing, Naama Kates about incels, and Chris Gabriel about YouTube. Read all of these pieces (and more!) here.

As you may have already gathered, I now have a regular column at RETURN—let me know if there’s anyone you think I should interview.

For Contra, I wrote “Mass Shootings and the World Liberalism Made.”

I feel compelled to defend myself here and say that I suspect people who leave comments like the one above didn’t read the piece. People get testy about that word, liberalism. It seems to trigger Cato Institute types who read the headline and immediately think, “she’s a delusional trad.”

I think they miss the point I’m trying to make because they only read the headline, though. Even if we go with the favorite ‘it’s mental illness’ line, it’s a mental illness engendered by our current circumstances. It manifests as gun violence in the United States because of the particulars of American culture and society. Of course, this is a point that’s explicit in the piece, as I do mention murderers in Europe and Canada.

Here's what should be the most important takeaway: if you take the dispositions, interests, and words of mass shooters seriously, then, yes, it does seem like the problem goes much deeper than “gun control” or “more therapy.”

Behind the paywall this week: abstracting hotness from appearance, TikTok’s least favorite mother and child duo Bebop and Bebe, intuitive labor, and a link to my Discord server.