Andrew Tate Is the Loneliest Bastard on Earth

thought digest, 01.21.2026

You’re reading default.blog. An emotional scrapbook of the Internet, technology, and the future.

Every five years or so, there’s a changing of the guard in digital media. Platform empires rise and fall, subcultures come and go, trends ebb and flow.

In my estimation, we’re entering year two of the latest shift.

The decline of punditry and traditional political commentary is continuing apace from its boom during Covid lockdowns. Commentators who might have once staked out clear, binary positions—conservative or liberal—are drifting away from political debate altogether, moving toward a more parasocial model: building audiences around personality and the feeling of relationship, rather than argument.

It’s increasingly clear that writing is niche. We’re moving away from the age of bloggers and Twitter, and into the age of streaming and clip farming—short video segments, often ripped from longer content, optimized for sharing. (I’ve made this point many times now, but this is why in the world of right-wing digital media, characters like Nick Fuentes are emerging as dominant, whereas no-video podcasters, bloggers, and Twitter personalities receive less attention.)

Labels like “right” and “left” are better thought of as “right-coded” and “left-coded”: ways of signaling who you are and who you’re with, rather than actual positions on what government should do. The people still doing, or more accurately “playing,” politics are themselves experiencing a realignment, scrambling to figure out new alliances as the old divisions stop making sense. I’ve written previously about New Old Leftists and the “post-right,” a motley group of former right-wing commentators who are not “progressives” in the traditional sense, but take up progressive points of view specifically in dialogue with their disgust with reactionary elements of the right.

Anyway, in this rise of coded communities—where affiliation is about vibe and identity more than ideology—we’re seeing the Manosphere go mainstream again. Second time? Third?

The Manosphere—if you’re a reader of this blog who somehow doesn’t know—refers to a loose network of communities organized around men, masculinity, dating advice, and self-improvement, sometimes tipping into outright hostility toward women. These communities have been around on the fringes of the internet for years, though depending on your vantage point, their underlying ideas are either hundreds of years old or at least sixty.

Either way, they keep surfacing into broader culture.

A Short and Non-Exhaustive Timeline of Moments the Pre-Internet Manosphere Penetrated the Mainstream:

The Manosphere as we know it today has at least two distinct antecedents. The first is the mid-twentieth-century convergence of pick-up artistry and men’s rights discourse: one responding to the Sexual Revolution and changing dating norms, the other developing in explicit opposition to second wave feminism. These strands framed gender relations as adversarial, strategic, and zero-sum.

The second antecedent is the part that I hear people talk about less often. The Manosphere in so many ways is a Black phenomenon. I do not mean this as a racial claim about ownership or blame, nor am I referring narrowly to what is sometimes called the “Black Manosphere.” I mean something more specific: many of the aesthetic forms, masculine philosophies, and anxieties that the Manosphere treats as “newly” discovered were articulated in Black American communities decades earlier. These were responses to economic exclusion, social displacement, and the erosion of traditional routes to masculine status.

Someone on X made the good point that the viral clips of Clavicular’s Big Night Out—Andrew Tate, Nick Fuentes, Sneako, and company—felt like a child’s idea of not only masculinity, but wealth. The cigars, the suits, the VIP table, the ham-fisted advice about how you don’t take women out to dinner.

If you’ve read Iceberg Slim, or watched 1970s blaxploitation films like The Mack or Super Fly, the visual language is immediately recognizable. You’ve seen this figure before: the fur coat, the Cadillac Eldorado, the exaggerated display of wealth and control. The question is why that aesthetic originally looked the way it did.

In mid-century America, Black men were systematically excluded from the institutions through which wealth and status quietly accumulate: country clubs, elite universities, corporate ladders, inherited property. The GI Bill’s housing provisions were administered in ways that shut out Black veterans. Union jobs in the building trades stayed segregated. The FHA explicitly refused to insure mortgages in Black neighborhoods. Under those conditions, conspicuous display wasn’t vulgarity (at least, not primarily or exclusively)—it was one of the few available ways to signal success in a society that denied access to the kinds of prestige that don’t need to announce themselves. When wealth can’t whisper—as TikTok’s “old money aesthetic” crowd loves to remind us it should—it has to shout.

The modern Manosphere inherits this aesthetic, adopting the symbols as though they were universal markers of arrival rather than compensatory performances forged under exclusion. What began as a response to being locked out of legitimate power gets recycled, abstracted, and repackaged, this time as timeless masculine truth. As so, to modern audiences, it reads as immature.

The aesthetic was codified in the late ‘60s.

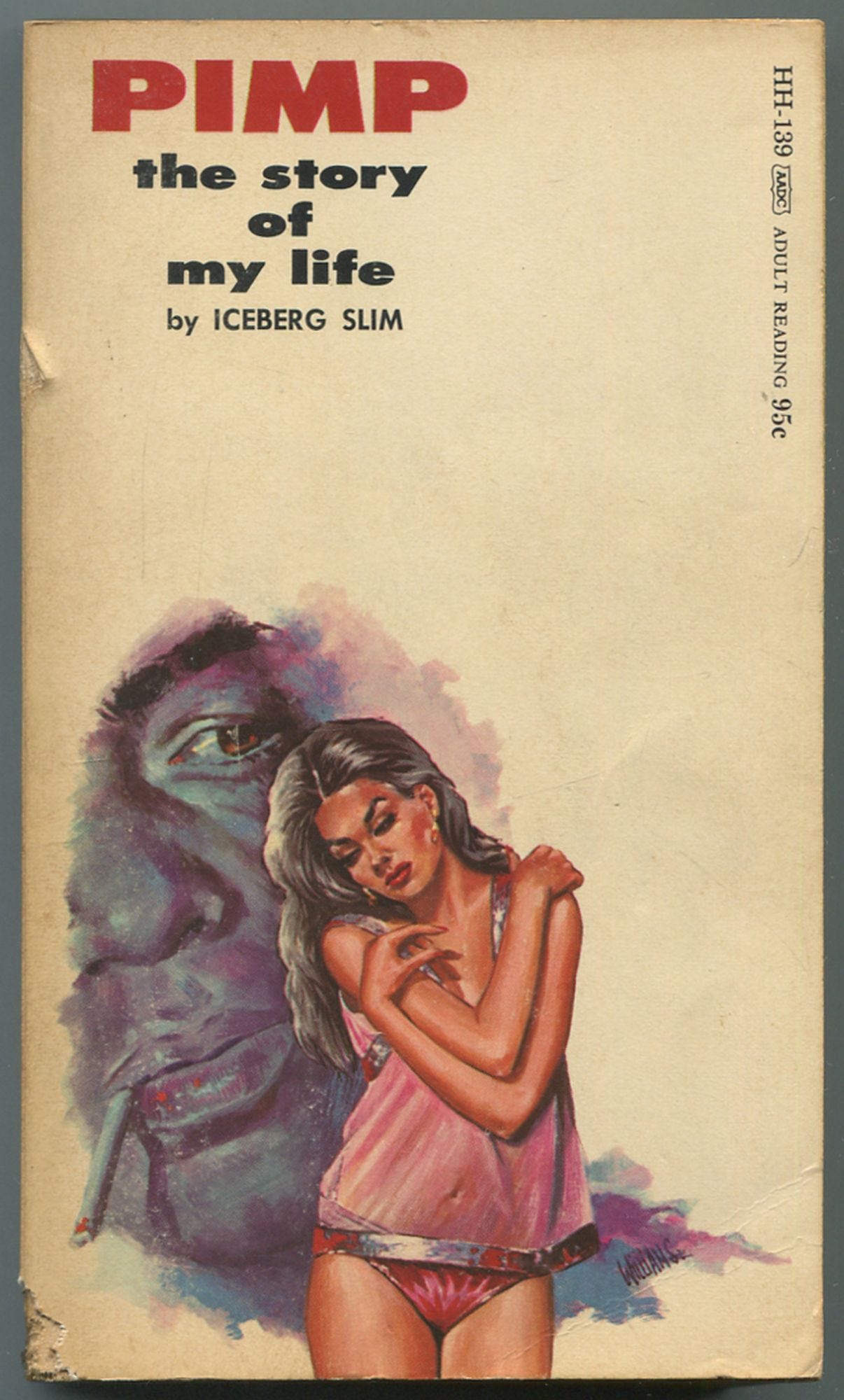

Robert Beck, better known as Iceberg Slim, published Pimp: The Story of My Life in 1967, just two years after the Moynihan Report was leaked to the press and became the subject of furious debate among civil rights leaders, Black nationalists, and white policymakers alike. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, then Assistant Secretary of Labor, had argued that the “deterioration of the Negro family” was at the heart of Black poverty, producing what he called a “tangle of pathology.”

The report was plainly racist, but both Slim’s book and the report were responding to the same thing: the economic foundations of traditional masculine identity were collapsing, and no one knew what would replace them.

The pimp, in Slim’s telling, is “the loneliest bastard on earth,” a man who must “be God all the way” to his women—never vulnerable, never soft, always performing omnipotence. Slim’s book became a template.

By the 1970s, blaxploitation films had transformed the pimp into an outlaw folk hero, emphasizing style over the moral complexity of the source material. What survived was the cool, the walk, the talk, the clothes, the attitude. Hip-hop — which I admittedly know very little about, so please feel free to correct me here —- picked up the thread: Ice-T named himself in tribute to Iceberg Slim; Snoop Dogg built an entire persona around pimp iconography; the rest is history. The pimp was no longer a figure of the Black underclass navigating impossible circumstances but was quickly becoming embraced as an inadvertent, unironic symbol of male success, available for adoption by anyone — race agnostic.

The “high-value man” who dominates contemporary Manosphere discourse is this same archetype, put through a respectability filter, or maybe just re-fit for modern tastes. The fur coat becomes a tailored suit. The Cadillac becomes a Bugatti. The stable of sex workers becomes a rotating roster of Instagram models (I guess, in Andrew Tate’s case, still sex [trafficked] workers). The underlying logic — and material conditions — are identical: women are resources to be managed, emotional detachment is strength, and a man’s worth is measured by his material display and his control over female attention.

The transmission is sometimes acknowledged openly. Manosphere forums routinely recommend Pimp as essential reading, noting that leading figures are simply teaching “old, street, pimp talk” in sanitized form. The oldheads in the Manosphere knows where its ideas come from. Gen Z and perhaps Millennials have simply forgotten why they emerged.

The genealogy becomes even clearer when you look at the women who serve as validators. Pearl Davis, the young white podcaster who has become one of the Manosphere’s most prominent female voices, follows a template established decades earlier by Shahrazad Ali, the Black author whose 1989 book The Blackman’s Guide to Understanding the Blackwoman provoked national controversy. Ali’s book arrived during the crack epidemic, as incarceration rates for Black men began their exponential climb and a sense of crisis pervaded discussions of Black family life.

What made Ali’s book so explosive—and so useful to her critics—was that she was essentially agreeing with Moynihan. Where Moynihan had argued that Black “matriarchy” produced a “tangle of pathology,” Ali argued that Black women had become unruly, disrespectful, and emasculating. Where Moynihan suggested that restoring Black male authority was essential to family stability, Ali argued that Black women should submit to male authority, accept male infidelity as natural, and return to traditional homemaking. She even suggested that Black men should occasionally slap their women into compliance. The diagnosis was Moynihan’s, dressed in the language of Black cultural nationalism. She appeared on The Phil Donahue Show to defend these positions to a stunned audience, and her book sold hundreds of thousands of copies despite being rejected by mainstream publishers.

Davis makes the same arguments stripped of their racial specificity: women are too independent, feminism has ruined them, they need to submit, their standards are delusional. The script was written decades ago, first by a white policymaker diagnosing Black “pathology,” then by a Black woman internalizing that diagnosis as cultural truth, and Davis is performing it for a new audience that believes it is hearing something novel.

The Manosphere’s grievances are not manufactured—just as the pimp’s weren’t. The anxieties it addresses are real. The conditions that produced the pimp archetype in Black America, the sense that legitimate paths to respect and provision have been foreclosed, are now conditions we all experience.

The Manosphere exists because millions of young men — of every race — are asking the same question Black men were asking in 1965: what does masculinity mean when its economic foundations have been removed?

Late in life, Iceberg Slim shared that he believed the game had damaged him — he had internalized a hatred of women stemming from childhood trauma, describing his pimp career as a prolonged act of self-harm. The pimp archetype emerged from real deprivation and produced more deprivation, never liberating anyone but redistributing suffering downward—not only onto women but to men.

Today’s Manosphere offers a diluted, algorithmic version of that same exchange, promising power through detachment, success through dominance, respect through performance.

This is what a man looks like when all other options have been foreclosed upon.

TOMORROW’S CALL-IN SHOW!!!

American Dreamland, my Coast to Coast AM-inspired call-in show with Taylor McMahon, is BACK tomorrow night at 7:30 PM Central. We stream here, on X, Twitch, Rumble, Kick, TikTok, and YouTube. If you’d like to be involved in our marketing efforts, please send me an email at katherine@default.blog. I am very irresponsible!

Tomorrow’s theme is THE MONSTER I LOVED. Call 775-288-8576 with your stories.

ME AROUND THE WEB

I was on [SIC] Talks today, looking adorable. Thank you Ben Dietz for having me!

A while back, I had the honor of going on the Reason podcast. I sound like an absolute lunatic here but I love their program.

The Spectator was kind enough to publish my eulogy to my father. I cannot tell you how much I miss him.

Friend reminded me of this classic, the OG PUA! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tuLRIMnGNoI

This post should really be widely talked about. It puts a problem in a historical perspective, and reframes the manosphere issue. Great writing!