I’m Katherine Dee. I read in an industry newsletter that I should re-introduce myself in every post. 😓 I’m an Internet ethnographer, sometimes podcaster, and reporter. I spend maybe 20 hours a week talking to people about how they use the Internet. It’s hard work. Consider sending me $5 for my efforts:

On today’s episode of The Computer Room, I talk to Philip Rosedale, founder of Linden Lab, not just about Second Life, but other synthetic lives.

I can’t stop thinking about synthetic life. I’m hopeful about it.

Imagine an entity born entirely in cyberspace—a literal entity, not a metaphor.

Or, maybe, as I put it to friends a few hours ago: imagine if ChatGPT had thoughts independent of its human users. Imagine that it was able to think outside of us. Imagine that an AI that was born not made, that it could age, that it had an entire, glorious life in cyberspace. A life outside of humans.

Would it have parents? What would an entity born and raised in cyberspace look like? Would we have to regulate the Internet to protect these beings, if not ourselves? Could it ever have an inner life? Could it have a “soul” without a body? How would this AI’s consciousness differ from our own human experience?

Imagine experiencing existence without the constraints of physical form, no body to separate itself from the world. What would it mean to have a soul made of information? What would it mean to age without a body? What would it mean for humans to create cyber-nymphs? What would it do to our faith?

Galileo's UFO

by A. R. Yngve

In 1610, the astronomer Galileo Galilei used his small telescope to observe Saturn directly. And he saw something that no other human had ever seen before.

He was not the first astronomer as such – for thousands of years, astrologers and other scholars had been studying those planetary orbits which could be seen with the naked eye. So Galileo knew that it had to be Saturn, appearing in its known orbit – but it had previously only been observed as a dot in the night sky.

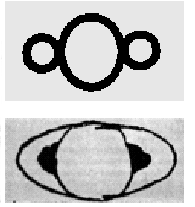

Saturn's visual appearance in his telescope was utterly unfamiliar, strange, hard to pin down. Galileo tried to draw what he saw directly (cameras did not exist at the time). His sketches, hand-drawn from observations made over several years, are fascinating. One of them depicts a planet with ”handles” attached to the sides. Another one tries to depict Saturn as a planet with two enormous moons impossibly close to it on each side. Both alternatives – a planet with handles! Planets bundled together like billiard balls! – must have seemed surreal to him, like a cosmic joke or a dream.

Today's historians have concluded that Galileo failed to identify Saturn's rings with certainty, because his telescope was inadequate. The Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens, using a much better telescope in 1659, finally deduced that what Galileo had struggled to perceive was a planet with a ring around it. It was the first such planet ever identified.

I want to argue that historians have been unfair to Galileo and his telescope. The greatest challenge for him, as the very first human to see a physical ring around a planet, was to understand what he was seeing. And this was not because of some faulty perception or intelligence on his part.

Imagine an alternate universe where the Earth's Moon had a ring which was highly visible from the Earth. And imagine an alternate Galileo in this universe, observing Saturn through his telescope for the very first time. This alternate-universe Galileo would have quickly recognized it as similar to what he and everyone else on Earth were already familiar with: a celestial body surrounded by a ring. Because he would have had a point of reference.

In order to truly see something that is unfamiliar to you, you first need a mental point of reference. We define and describe things in relation to other things. The further away new sights are from familiar points of reference, the harder it is to perceive them clearly. Since the real Galileo saw, for the first time, something which he could not compare to any other celestial object, he struggled to identify it. Sometimes it seemed like one thing to him, sometimes like another. In other words, Galileo's first observation of Saturn's rings was a UFO (Unidentified Flying Object).

Today, our scientists and military observers struggle in a way akin to Galileo's troubles with Saturn's rings. UFOs are being observed, on modern cameras with tracking systems – and yet, humans cannot quite define what their instruments are seeing. Sometimes the UFOs look like one thing, sometimes like another.

While most UFO observations can be explained as a misinterpretation of known phenomena, the truly unexplained cases remain. Our minds try to find a point of reference to define these ”true” UFOs. A popular one is that they might be spaceships from some unknown alien civilization. Let's be honest: We can't know that for sure, because the only alien civilizations we can think of are lifted from science fiction. A reference point more ”tangibly alien” than fiction does not exist – yet.

In the absence of a solid reference point to make sense of these observations, an entire culture of ”placeholders” for an explanation has grown over time: Aliens that have never been captured on camera; saucer-shaped spacecraft that have never been sampled or examined; alien encounter narratives that never come with solid evidence to back them up.

However: In this culture of ”placeholders” I would also include the ”debunkers” of UFOs. They have the advantage that even though they also lack a point of reference to define a UFO, they can comfortably choose ”placeholders” which sound more familiar, and thus more credible: Misinterpreted birds, aircraft, drones, planets, satellites, secret military prototype craft, balloons, clouds, hallucinations, fraud, etc.

Every layman has seen a bird, or a plane, so that sounds tangible. Except that the ”true” UFOs do not behave like birds or planes – or anything we're familiar with. Even ”drone” is a placeholder until the UFO resembles the drones that we know exist today. (Personally, I would not even grasp for the ”spaceship” placeholder.)

The problem remains: How to define, and thus perceive, that which does not resemble anything we recognize from before.

And to argue that UFOs cannot be real because ”obviously” we could describe them if they existed, is to make an error of assumption: That everything that exists can be seen in a way that makes sense to the human mind, regardless of reference points. If that is true, why didn't Galileo quickly identify Saturn's rings?

Here is a more recent example of something ”undescribable but real” in science: Ask a physicist to define what a quark – the smallest known part of an atomic nucleus – really is, or what it looks like.

An honest physicist will reply that only certain properties of quarks can be measured (mass, charge, spin, etc.), but quarks themselves cannot be objectively described in human language – because no meaningful points of reference exist. (Shape? Surface texture? Color? Hardness? Interior structure?)

Quarks exist in the sense that they fit the theory, and fit the observations made in experiments, of how protons and neutrons behave. (If a better theory comes along, quarks may cease to exist.)

We do not know what quarks look like, and we may never know. (They are not tiny colored balls.) Their existence has only been proved indirectly, through particle-collider experiments.

With the above example in mind, you can see why we should not dismiss UFOs as imaginary only because we cannot clearly describe them. That would be just as wrong as to claim we do know with certainty what they are.

A more thorough and persistent scientific examination may yet come up with new facts that could make sense of the phenomenon. The uncertainty itself does not equal a proof for, or against, UFOs.

The physicist Avi Loeb is sincere in his attempts to find physical evidence for UFOs. And I find his willingness to explore the unknown admirable – but it's possible that he, too, might be led astray by mental ”placeholders.” What if UFOs could be something even stranger than spaceships from another star system? What if they, like quarks, are physical phenomena so utterly different from our frame of reference that we cannot perceive them as they are?

A variation on the argument that UFOs are unfamiliar beyond our experience goes as follows: A hypothetical alien intelligence might be so far advanced that it is incomprehensible to us, too mentally overwhelming. Thus when it is present, in the form of a UFO observation, we're like goldfish trying to make sense of what is visible outside the aquarium. We become aware that ”something” is there, but it remains vague and elusive. The problem with this argument is that it encourages us to give up; any effort to understand UFOs is inherently futile. That has not been proved.

Galileo could have dismissed what he first saw in his telescope as hallucinations, or a technical error, or simply too overwhelming, instead of persevering despite his confusion. How would that have slowed down the progress of astronomy? Christiaan Huygens did not confirm the discovery of Saturn's rings in a vacuum; Galileo's pioneering efforts had inspired others. And this was during a time when astronomical discoveries were suppressed by the religious establishment, because they challenged medieval dogma. Galileo dared to try and see what was not only unknown, but religious taboo.

Galileo showed by his example that we should not settle for ”placeholder” knowledge, but should keep seeking a truer, better understanding. The obstacle to that understanding was summed up in Marshall McLuhan's aphorism:

”I wouldn't have seen it if I hadn't believed it.”

References: