Katherine Dee, also known by her pen name, “Default Friend,” is one of the most original culture commentators of her generation. She’s an Internet archaeologist, a fandom taxonomist, Marshall McLuhan’s clearest heir … a unique voice. She made her name with, among other things, a theory about how Tumblr changed US politics. Today, she is writing about the new forms of art and culture that the Internet has spawned.

As we covered on this week’s CrowdSource newsletter, many critics today believe that culture is at a standstill, decadent, and out of ideas. But Katherine believes that those critics are failing to notice a new kind of culture developing on social media. She makes her analysis in her usual, dispassionate way. She is less interested in making moral judgments than in making an accurate, objective description of what is going on. And what is going on is, for better or worse, fascinating.

— Santiago Ramos

The idea that culture is stagnating, as Ted Gioia puts it — or that it’s stuck, as Paul Skallas says — isn’t new. Neither is the observation that there’s something different about how bad things are in this particular moment. The cultural malaise is palpable and cross-generational. The complaints are more than just “old man yells at cloud.” Everyone feels it.

Consider film and television, an easy target for cultural pessimists, and for good reason. The signs of decay are hard to ignore. If it’s not the slurry of superhero blockbusters, remakes and reboots, then it’s the straight-to-streaming slop. The familiar three-act structure, that is the craft of screenwriting, seems mysteriously missing from even successful films. Will Gluck’s Anyone But You stands out as a notable example of a movie that was enjoyable in bite-sized pieces on TikTok, but lacked many of the hallmarks of traditional filmmaking. Crew members frequently take to social media, posting teary-eyed videos about the scarcity of jobs in Hollywood — “it’s dead.” Industry decline has also affected indie films, which don’t enjoy the same distribution channels they once did.

The publishing world isn’t faring much better. Mainstream offerings are dominated by sensationalist non-fiction, formulaic and #BookTok-approved YA, and an endless parade of self-help. The few compelling books still being published for mainstream audiences occupy niche spaces, without the broad public engagement they once enjoyed. If intellectuals have always complained about the fragmentation or diminishment of the reading public, today the situation is dire. It’s not that people aren’t reading: many of them don’t even know how. It’s plausible that many serious readers, and certainly writers, know one another, if not in person, then through X and Substack.

Fashion and music, too, are in decay. Trends are still identifiable, but they lack the clear demarcations of previous decades. Based on clothing styles alone, a photo taken in 2013 could be mistaken for one taken in 2019, a creative stasis unthinkable even thirty years ago. Maybe it’s the rapid cycles of fast fashion, or our smartphone-first social culture which keeps many of us isolated, or maybe we’ve simply grown accustomed to digital photography’s age-concealing effects —a contrast to film photos that more readily showed signs of aging. (Interestingly, makeup trends have evolved more distinctly, perhaps because they adapt better to the nature of social media.)

In music, Ted Gioia writes that old songs are killing new ones. We chalk that up to a tendency towards curation or remixing, but we’ve also witnessed a shift with how we listen to music. In just under one generation, we moved from appreciating albums as cohesive works to consuming individual tracks, and then to music becoming reduced to muzak: background noise for gaming, viral videos, or endless scrolling. Disappearing is music as an art in its own right, which commands sustained attention and deep engagement. A song’s success is measured not by critical acclaim but by whether their song goes viral or becomes the “soundtrack” to someone’s life.

If you complain about these trends, the responses you’ll get typically fall into two camps. One sympathizes with you, but offers only a resigned “How are you just now noticing?” The other dismisses your concerns as a symptom of aging. There’s plenty of great music, movies, literature, and fashion, and if you don’t like it, that’s your inability to keep up.

Both responses miss something important, though. They both assume that what we know as “culture” is the only type of culture that could ever exist.

There’s a third possible response, and that’s that there’s a new culture all around us.

We just don’t register it as “culture.”

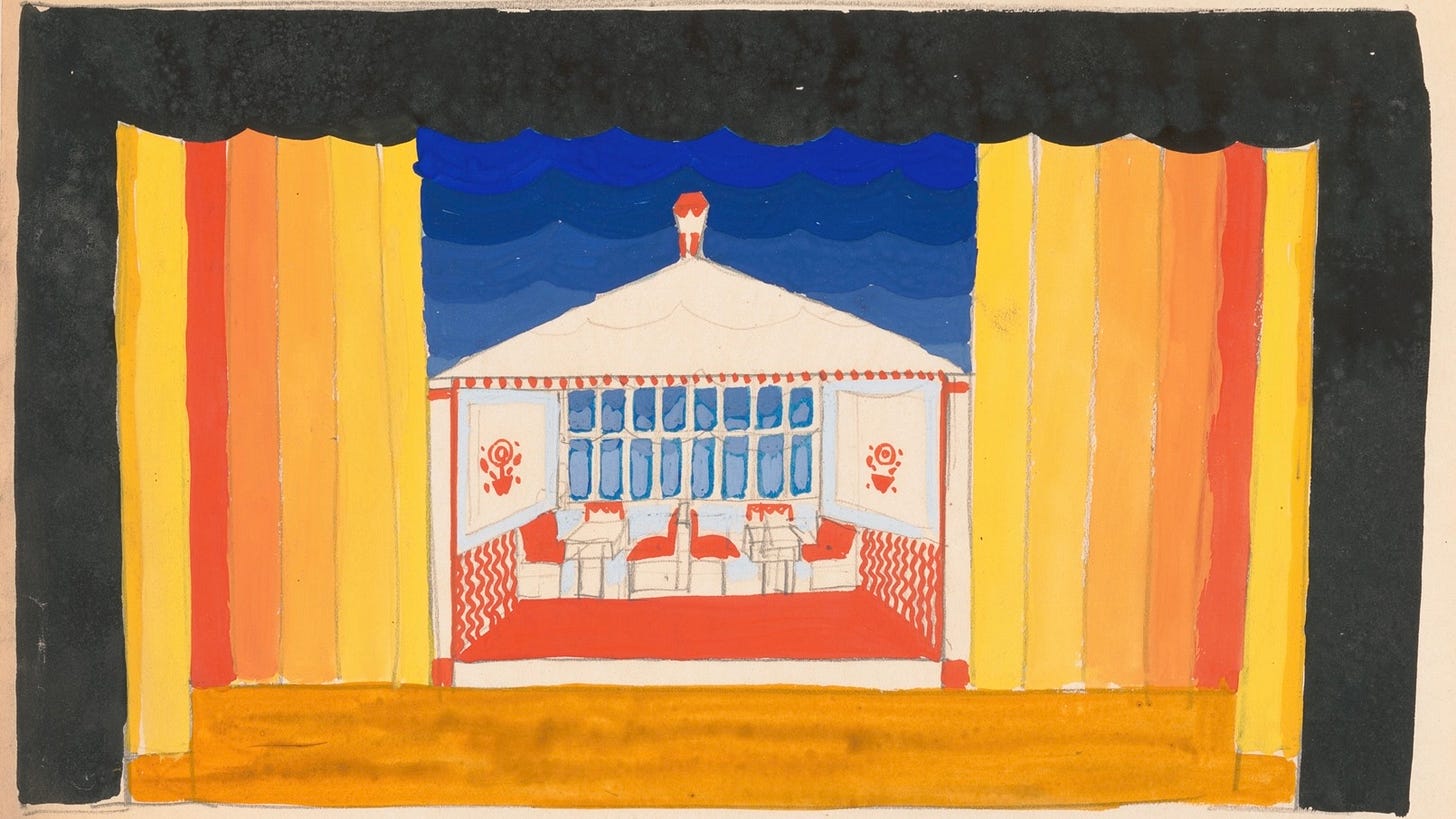

Theater is a good example of what I’m talking about. Once a dominant art form, theater ceded its cultural primacy a long ago. People still produce and even write excellent plays and musicals, even today, but it’s no longer the primary vehicle for cultural expression and innovation. It’s a niche. Similarly, film, fashion, literature, or even music as we once knew them are no longer the primary mediums through which new and exciting culture is experienced. They haven’t completely gone away, but the landscape has changed so radically that they shouldn’t be the metric we use to measure the progress of culture.

We’re witnessing the rise of new forms of cultural expression. If these new forms aren’t dismissed by critics, it’s because most of them don’t even register as relevant. Or maybe because they can’t even perceive them.

The social media personality is one example of a new form. Personalities like Bronze Age Pervert, Caroline Calloway, Nara Smith, mukbanger Nikocado Avocado, or even Mr. Stuck Culture himself, Paul Skallas, are themselves continuous works of expression — not quite performance art, but something like it. They may also be influencers, or they may not be, but the innovative aspect isn’t that they're promoting a brand or making money from their venture. It’s not about their single tweet, self-published book, or video. The entire avatar, built across various platforms over a period of time, constitutes the art. Their persona must be enjoyed in the moment, as it reveals itself on the platforms; the audience response is part of the piece. The way their audiences start to speak like them, the aesthetics they inspire, and the way they shape headlines — this is all social media born culture.

The Internet-Personality-as-Art is ephemeral, challenging, and doesn’t even register as a performance to most critics. Most of it is considered throwaway trash by casual viewers. Crucially, many of those viewers would be correct: not every social media personality is well-constructed, and not every example is art, in the same way not every movie is good. This may be the biggest obstacle for these new cultural forms: much of it is terrible. But in rejecting the form completely, in laughing at the idea that it might be innovative, we overlook the works of genius.

The same is true of TikTok. It’s a mistake to dismiss TikTok as the “dancing app” or “digital fentanyl” or a machine for political brainwashing. Yes, it’s true that many viral TikToks aren’t worth their minute-long (or longer, as is now the case) runtime. But there is a lot of innovation on TikTok — particularly with comedy.

TikTok sketch comedy is in the same lineage of theater. It invites a suspension of disbelief from the audience, creators often play multiple characters, rapidly switching between roles with nothing more than a change in voice, facial expression, or camera angle. And importantly, it’s funny. When the whole feed is taken together, it’s almost digital vaudeville: a song, a short sketch, a physical feat, slapstick, animal acts and satire, one after another, in a personalized variety show on your phone.

The dismissal of TikTok suggests another source of confusion: these new cultural forms are challenging our ideas about how culture “should” be created and distributed. The Internet was supposed to democratize everything, do away with gatekeepers and in some cases, craft. We were prepared for that: the masses overtaking the institutions.

But that’s not what happened. The gatekeepers and the craft both changed. And with it, so did ideas around authorship. It wasn’t a simple fight between independent creators and established ones. It was a complete reshuffling.

It’s a spectrum. At one end, we have Internet Personalities, with their cults of devotion. In the middle, we find fan culture, where some fans become prominent figures within their fandoms, stars in their own right. These Big Name Fans occasionally break out to create their own media kingdoms, as was the case with E.L. James, who authored Fifty Shades of Grey, itself originally Twilight fanfiction, and Cassandra Clare, who began in the Harry Potter fan community, before going on to write several popular fantasy series. At the other end of the spectrum are anonymous creators, whose approach to authorship is almost medieval: their projects are not about them as individuals, but the meme, the project, the aesthetic, the vision. They are less like the expressive individualists of Modern art, than the cathedral builders of the Middle Ages.

Much has been said about memes as art and the collective labor and imagination that goes into their creation, but it extends further than that. It’s not just memes. Creating mood boards on Pinterest or curating aesthetics on TikTok are evolving art forms, too. Constructing an atmosphere, or “vibe,” through images and sounds, is itself a form of storytelling, one that’s been woefully misunderstood and even undermined as shallow. Many of these aesthetics have staying power, like “coquette” and “cottagecore.” They’re not passing fads or stand-ins for personalities or subcultures. They are more than ever-evolving vectors for consumerism. They’re a type of immersive art that we don’t yet have the language to fully describe.

But that is the case with so much of what’s new. We won’t understand it until it’s in the rearview mirror. Culture isn’t stagnating; it’s evolving in ways that we’re struggling to recognize and appreciate. The challenge lies not in reviving what’s dead, but in developing the language to understand what already exists.

See also:

Wisdom of Crowds is a platform challenging premises and understanding first principles on politics and culture. Join us!